Seventeen Verses of Genealogy

In the run up to Christmas, many will begin reading the story from Matthew 1:18, “This is how the birth of Jesus Christ came about…”. This is a natural place to begin but why did the gospel writer, Matthew, not begin his account there? Why did he start with seventeen verses of genealogy?!

It is generally accepted that Matthew’s primary audience was Jewish. What was important to them – and, necessary for us to understand too – was that the good news he was about to tell was the fulfilment of a much longer story that began many centuries before. The Jewish hope centred around a genealogy, because they were promised a child from the family of Israel.

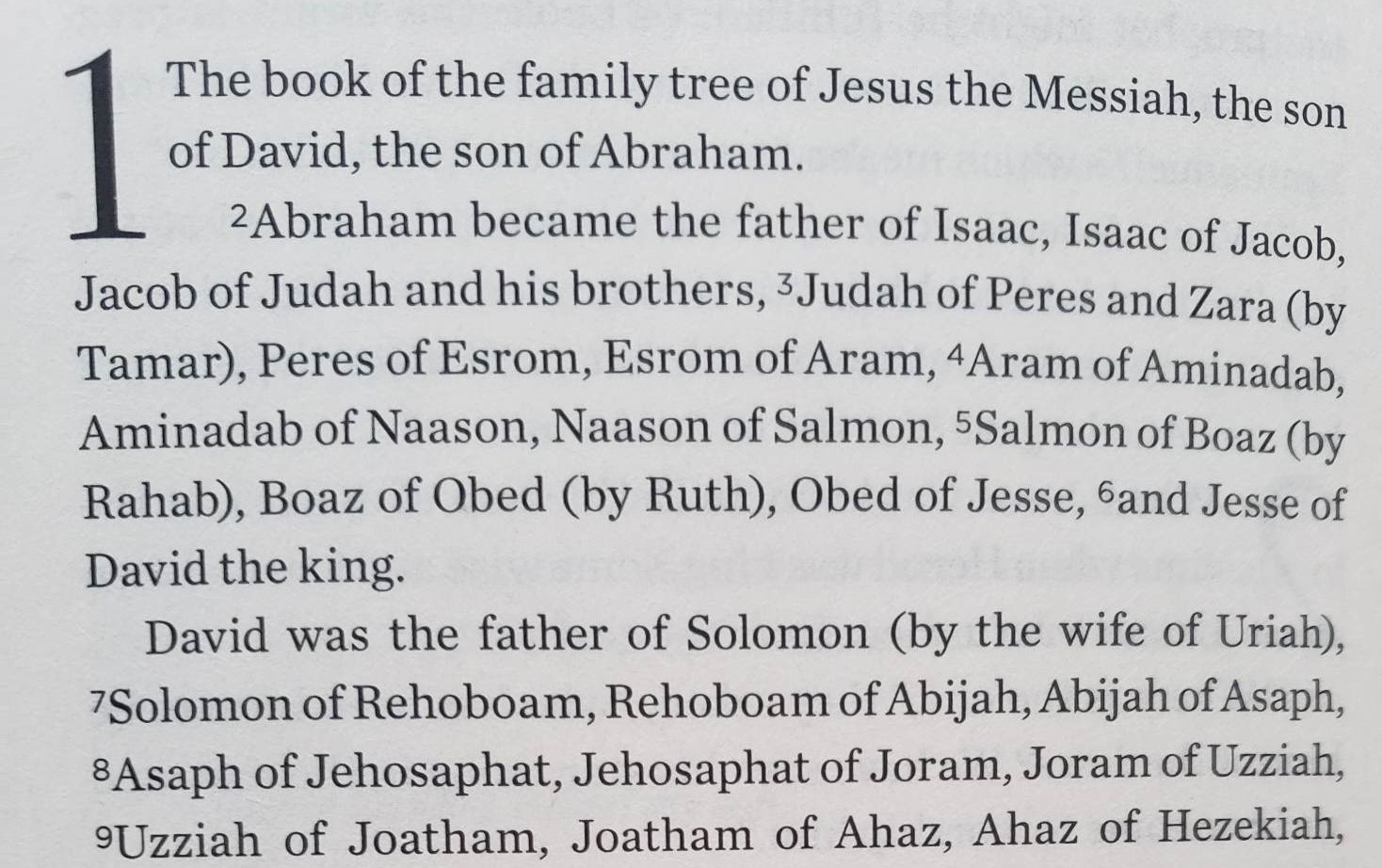

Matthew’s opening verse sums up the whole story: “Jesus, who is the Messiah, was the son of David and the son of Abraham.” These two names then become the key markers for the three main sections of his story recorded in what we know as the Old Testament:

– from Abraham to David (14 generations);

– from David to the Babylonian exile (14 generations);

– from the exile to Jesus himself (14 generations).

Interestingly, Matthew highlights the fact that this Old Testament history falls into three approximately equal spans of time. Symbolically, three double-sevens means real completion or perfection.1

Let’s take a brief look at their significance within God’s plan of redemption.

Jesus was the son of Abraham

After the early chapters of Genesis portray the rebellion of the human race against God’s love and authority (at individual, family and societal levels), in chapter 12 we are introduced to seventy-five year old Abram who is later named Abraham, as through his descendants “all the nations of the earth would be blessed.”

After Abraham is chosen as the founding father to kick-start God’s universal mission project, God selects one nation to be the means of blessing all nations. This isn’t about favouritism. The Old Testament nation of Israel exists for the sake of all the nations of the world (at the time, seventy nations are listed in Genesis 10).

Returning to the genealogy, not only is Matthew using it to show that Jesus is a ‘real’ person – a Jew, with a real ancestry – he is also showing that as the Messiah, Jesus has come to make that promise, initially given to Abraham, a reality at last.2

Significantly, the Messiah’s Jewish ancestry also highlights the fact that it includes Gentile blood as well, with the listing of four mothers – Tamar, Rahab, Ruth, and Bathsheba. The fact that this family tree highlights, rather than conceals, children born out of incest, prostitution and adultery, seems to prepare us for something even more unexpected, the virgin birth.

Jesus was the son of David

As well as Jesus being the true ‘son of promise’ (Isaac being the OT type), Matthew also makes clear that Jesus the Messiah was from the royal line of David. As the Davidic king, the Messiah’s rule would mean justice, liberation for the oppressed, the restoration of peace among mankind and in nature itself. To David were made promises of future lordship over the whole world.3

With David we see a partial fulfilment of God’s covenant with Abraham. Abraham’s offspring have become a great nation; they have taken possession of the promised land; and they are enjoying their special covenant relationship of blessing and protection with Yahweh.

Now there is a royal, kingdom dimension as the story progresses into the next phase.

Under King Solomon’s reign the temple becomes the focal point of God’s presence with His people. However, the story of Israel becomes divided into two kingdoms (Israel in the north, Judah in the south), with the northern kingdom ceasing to exist following the attack of the Assyrian empire.

The list of kings continues until the Babylonian empire replaces Assyria and rebellious Judah goes into exile with the fall of Jerusalem in 587 BC. This brings to an end to the second section of Matthew’s genealogy in verse 12.

From the Exile to the Messiah

After a fifty year exile, Persian King Cyrus defeats Babylon and the return of some of the Jews begins as a small sub-province of the vast Persian Empire. The record of Old Testament history comes to an end with Malachi, Ezra and Nehemiah. But the Jewish community (and Matthew’s genealogy) continues during the four hundred year intertestamental period with two more imperial changes (first with the Greeks and then with the Romans).

It is into the time of the Roman empire that Jesus the anointed and long-awaited Messiah arrives, to complete the Old Testament story. Jesus’ birth is what Israel had been waiting for for two thousand years.

Old Testament Importance

Matthew’s genealogy therefore connects the Old with the New. It shows us that the Old Testament is still important and not to be viewed as no longer relevant.

In fact, it is vital to understanding and interpreting correctly what follows in the New.

It highlights the faithfulness of God to keep His promises and fulfil all the prophecies spoken beforehand.

Jesus’ own understanding of Himself is rooted in the story of Israel as told in the pages of the Old Testament. The writings of Paul and the other writers of the NT are also rooted in the Hebrew Bible.

All About Jesus

Furthermore, as Jesus would later make clear, the whole of the Old Testament testified about Him (Luke 24:27, 44-45; John 5:39)). At Christmastime, let’s realise that the Jesus story begins much earlier than with His birth in Bethlehem. In fact, it begins even before the Creation account in Genesis 1.4

The truth of the matter is that the whole of the Old Testament is about Jesus Christ. Matthew compresses it into 17 verses. Jesus later condenses it into a single parable about a vineyard and its tenant farmers. On the road to Emmaus, He gives His fellow travellers a two-hour Bible study explaining how the Law and the Prophets were all about Him. How I wish I had been able to tag along for that lesson in an overview of the whole Old Testament!

New Beginning

Finally, Matthew’s genealogy follows four hundred years of silence (the intertestamental period between the Old and New Testaments). Light is now penetrating the darkness. God’s story and His eternal plan is coming to pass.

In Jesus Christ, His genealogy becomes our family tree. “The book of the genealogy” (Matthew 1:1) can be translated ‘the book of Genesis’. It is a new beginning. A child has been born whose kingdom will endure forever. A new Adam who will establish the new creation.

Why Matthew’s Genealogy is Important

So, in summary, why is Matthew’s genealogy so important?

1. It explains the Old Testament story simply into three sections of history which culminate in Jesus. As my singer/songwriter wife put it: the three sections (Abraham, David & exile) are the verses culminating in the chorus, which is Jesus!

2. It shows us Jesus is not a myth but a real person, who is relatable and is for all people (Jew and Gentile), whatever their racial, ethnic, or moral background.

3. It connects us into the bigger story, as in Jesus Christ His genealogy becomes our family tree too! We are the heirs of the promise to Abraham. We are heirs of God’s eternal kingdom, foreshadowed with David. We have been redeemed out of exile and restored into God’s family. God no longer dwelling in man-made temples, but dwelling among5 and within His people. Emmanuel, God with us!

1 It is not strictly accurate as several biological generations are skipped over, but this was quite common in OT genealogy. Matthew is more interested in being deliberately schematic to present the critical events within three approximately equal periods of time. There is also another reason Matthew chose 14. In Hebrew, David consists of three letters (DVD) and has the numeric value of fourteen (dalet [4] + waw [6] + dalet [4]). Matthew is therefore tracing Jesus’ genealogy to show and reinforce the point that Jesus is the heir of David.

2 Jesus stated, “Your father Abraham rejoiced to see my day, and he saw it and was glad.” (John 8:56).

3 2 Samuel 7:12-16; Isaiah 9:6-7; Jeremiah 23:5; Luke 1:31-33.

4 See 2 Timothy 1:9; 1 Peter 1:20.

5 John 1:14.

Source: Knowing Jesus Through the Old Testament by Christopher J. H. Wright, 2014